I

first learned about loveys from the Peanuts cartoon character, Linus. His lovey—his

blanket—goes everywhere with him.

http://www.simonsaysstamp.com/catalog/peanutslinus1065.jpg

Both

my daughters had loveys. Like

Linus, Mary had a blanket—she called it Temply Blankey. It went everywhere with her until it

failed to return home after a birthday slumber party. Sarah also had a lovey—Ted E. Bear. A baby gift from one of

my math-teaching colleagues,

Teddy was bigger than Sarah when she was

born, and almost as big as her when she first began lugging him around. Dressed in one of her toddler t-shirts,

Teddy went everywhere with Sarah. So

when Sarah entered the 2 ½ year old class at Anderson Mill Baptist Church Child

Care, so did Teddy. Soon Teddy was

a full-fledged member of the class—but not just any member. For Teddy was the one who tried things

first, showing the other students it was safe and fun. When the class read Green Eggs and Ham and their teacher

encouraged them to taste some green eggs, Teddy tasted first. When he did not make a face, the other

students tried and liked them. On cooking day, Teddy was the first to

try pouring the batter. When Teddy

did not get burned—staying the appropriate distance from the griddle—the other

students were ready to try their hands at making pancakes, too. Over the years, Teddy accompanied Sarah

to summer camps and college and even to seminary this year.

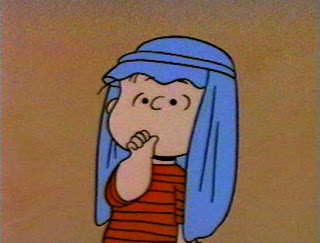

Loveys,

like Linus’ blanket can be very important to us. In “A Charlie Brown Christmas,”

when his sister Lucy threatened to confiscate it during practice,

Linus fashioned his lovey into his

Christmas pageant costume—shepherd’s headgear.

http://pics.livejournal.com/greatest_ever/pic/0000gcdz

In

today’s text, Jesus says, “I am the Good Shepherd.” Unlike the men and women of his day, we are not a pastoral

people. Although some of our

congregation are farmers, and several of you grew up on farms, and many of you

tend backyard gardens, we are not a pastoral people. The lives of most of us 21st century Americans do

not revolve around herding livestock; our lives do not revolve around the

changing availability of water and pasture. So we need some help in understanding what the term shepherd might have meant to Jesus’ audience,

what it might have meant to the community in which the gospel according to John

was written, and what it might mean for us.

John

sets this speech from today’s scripture in Jerusalem. Listening to Jesus are his long-time followers from Galilee,

pilgrims who have traveled to Jerusalem for the Passover, and religious

authorities—Pharisees, scribes, and priests. All of them Jews, they share common knowledge of the

shepherd motif in both Jewish history and Jewish beliefs. Like the great

emancipator—Moses, and the mighty king—David, the kings of Israel were supposed

to shepherd the people—to lead them in right worship of God and to care for

them—providing them with sustenance and protection.

The

prophet Ezekiel claimed it was because the kings had failed to shepherd the

people—rather than protecting and providing for them, they had endangered and

exploited their flock—the prophet Ezekiel claimed it was because the kings had failed

to shepherd their people that God stripped them of their power and allowed

Israel to be overrun and the people to be exiled. The prophet Ezekiel claimed it was because the kings had failed

to shepherd the people that God promised to be their True Shepherd. Even though they were exiled in

Babylon, God would seek the people out, care for them, and ultimately return

them to their homeland. They would

be God’s flock.[1]

So

when Jesus says, “I am the Good Shepherd,” two pictures probably come to his

listeners’ minds. First, they see

the failure of their appointed leaders—the temple leadership there in Jerusalem—to

shepherd the people. The religious

leaders are the hired hands that run away and leave the sheep unprotected like

the kings of Israel had done.

Second, his listeners connect Jesus the Good Shepherd with God, the True

Shepherd.

And

what about the community for whom this gospel was written? At the end of the 1st

century AD, when it was penned, “the life of a shepherd was . . . dangerous,

risky, and menial. Shepherds were

rough around the edges, spending time in the fields rather than in polite

society.”[2]

Shepherds were marginalized, considered outsiders—perhaps like today’s migrant

workers. This gospel was written

within and for a community of Jewish Christians whose belief that Jesus is the

risen Christ brought persecution upon them. Labeled as heretics, they were forced to choose between

following the Christ or remaining in their religious, economic, social, and

kinship community. Kicked out of their

synagogues because of their faith in Jesus, they relate to the shepherd who is also

an outsider. Considered strangers to their families, they connect with the

shepherd who knows his own and whose flock knows him.

And

what about us? How does the good

shepherd metaphor speak to us? If

Jesus is the Good Shepherd, does that make us—his followers—sheep? And do we want to be sheep? We—Kansas is known for beef & Texas

is cattle country—we may have some bias against sheep. Here’s what I learned

about sheep in my sermon preparation.

Unlike cattle, which you can prod and push from behind, sheep prefer to

be led.

http://www.jesusmafa.com/anglais/imag31.htm

They “will not go anywhere that someone

else—their trusted shepherd—does not go first, to show them that everything is

all right.”[3]

That reminds me of Ted E. Bear, Sarah’s lovey that showed her little pre-school

classmates that it was safe to cook with the teacher. And it was fun to try out the new and different foods. I do not intend to reduce the Good

Shepherd to a lovey. But like a

lovey, the Good Shepherd provides reassurance that we are safe. We are held in the strong, loving arms

of the Good Shepherd.

I

also learned that sheep form an attachment, a relationship with their shepherds.

Robyn Eversole. Red Berry Wool. Paintings by Tim Coffey. Morton Grove, IL: Albert

Whitman & Company, 1999.

Robyn Eversole. Red Berry Wool. Paintings by Tim Coffey. Morton Grove, IL: Albert

Whitman & Company, 1999.

Jesus says, “I am the Good Shepherd. I

know my own and my own know me, just as the Father knows me and I know the

Father.” “We all long and

hunger to know and to be known.”[5]

We all long and hunger for relationship.

Jesus offers a relationship between him and each one of us with the same

intensity as that between Jesus and the one whom he refers to as Abba—Daddy. As the Good Shepherd, Jesus offers to

share with each one of us the same level of mutuality, the same level of

knowing as he shares with the one he calls Father.

Jesus

says, “I am the Good Shepherd. I lay down my life for the sheep.” He does not say, I lay down my life for

my

sheep but for the sheep. “It is an inclusive, rather than an exclusive, gift,

just like God’s love for the world.”[6] He continues, “There will be one flock, one shepherd.” Not only does Jesus offer a loving, trusting relationship

between him and each one of us, but also he offers this relationship to the

community—the community of faith, the community of believers. He offers this relationship to our

community, which we claim is open to all of those seeking to know Jesus the

Christ.

The

Good Shepherd lays down his life, of his own accord. No martyr against his

will, but instead one in control of his own death, Jesus the Good Shepherd is

Jesus the Crucified One. The Good Shepherd lays down his life in order to take

it back up again. No helpless

victim, but instead one with power over all that would destroy—even death

itself—Jesus the Good Shepherd is Jesus the risen Christ.

Enfolding

us in his loving arms, the Good Shepherd leads us through life—through the

comfortable and the difficult, through the restful and the busy, through the

joyful and the despairing. He

accompanies us in the darkest of times.

Giving generously, he provides for more than our necessities. He pursues us with his steadfast love

all the days of our lives.

Wrapping

us in the folds of a lovey—the community of faith stitched together with the

threads of his love—the Good Shepherd, draws us together. Together, we, the flock—as one—accompany

each other through life—through fast-paced days, weeks, months, years of

activity and through long, endless times

of loneliness; through successes and failures. Together, we, the flock—as one—walk with one other through

the darkest of times, holding each other’s hands until we, together, finally

set foot in the light again. The

Good Shepherd calls us into community, fashioning us to do as he does—to

accompany, to provide for, and to love.

[1]

Ezekiel 34.

[2]

Nancy R. Blakely. “John10: 11 –

18—Pastoral Perspective,” in Feasting on

the Word, Year B. vol. 2. Edited by David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor. Louisville: John Knox Press, 2008.

p. 450.

[3] Nancy R. Blakely. “John10: 11 – 18—Pastoral Perspective,”

in Feasting on the Word, Year B. vol. 2. Edited by David L.

Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor.

Louisville: John Knox

Press, 2008. p. 450.

[4] Nancy R. Blakely. “John10: 11 – 18—Pastoral Perspective,”

in Feasting on the Word, Year B. vol. 2. Edited by David L.

Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor.

Louisville: John Knox

Press, 2008. p. 450.

[5] Barbara

J. Essex. “John10: 11 –

18—Homiletical Perspective,” in Feasting

on the Word, Year B. vol.

2. Edited by David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor. Louisville: John Knox Press, 2008.

p. 451

[6] Gail R. O’Day, “The Gospel of John,” in The New Interpreter’s Bible, a Commentary in

Twelve Volumes. Vol. IX.

Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1995.

p. 673.

No comments:

Post a Comment